The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) recently issued a statement in which they will require all drones or Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) above a certain weight to be compatible with a new standard. They refer to the new rule as UAS Remote Identification (Remote ID) or RID. Remote ID uses radio waves to actively transmit information about an object in order to help track and/or locate the object.

“Remote ID helps the FAA, law enforcement, and other federal agencies find the control station when a drone appears to be flying in an unsafe manner or where it is not allowed to fly. Remote ID also lays the foundation of the safety and security groundwork needed for more complex drone operations.”

These RID transmissions will be readily available to the public and easily consumed by existing devices such as cellphones, tablets, or personal computers potentially by Wi-Fi broadcasts. Drone manufacturers have 18 months from the rule’s effective date (which has not been determined) to implement the technology.

What About the Drone Pilot?

AeroDefense supports the FAA's new requirement for RID broadcasts in concept. Just as vehicles require license plates to be visible for public safety, drone pilots should be responsible and liable for actions they take. Enforcing something like an RID is a good first step. There are, however, some downsides to consider.

The first is a concern for the privacy of the pilot. While a license plate is visible on a car, it does not actively transmit its ID and location for all in the area to track and monitor. Some drone pilots may not be comfortable with sharing their location for the world to see. Professional pilots may consider their flight location and times competitive information they don’t want others to know.

On another note, the RID, just like a license plate, only works for drones piloted by people who follow the law. Anybody can take the license plate off their vehicle just as easily as they can disable the RID on their drone. Police will certainly stop a vehicle driving around without a visible license plate. Drones on the other hand do not have anything visible to the human eye that can monitor if their RID is enabled, something nefarious drone pilots will quickly realize and use to their advantage.

Where Does Drone Detection Come In?

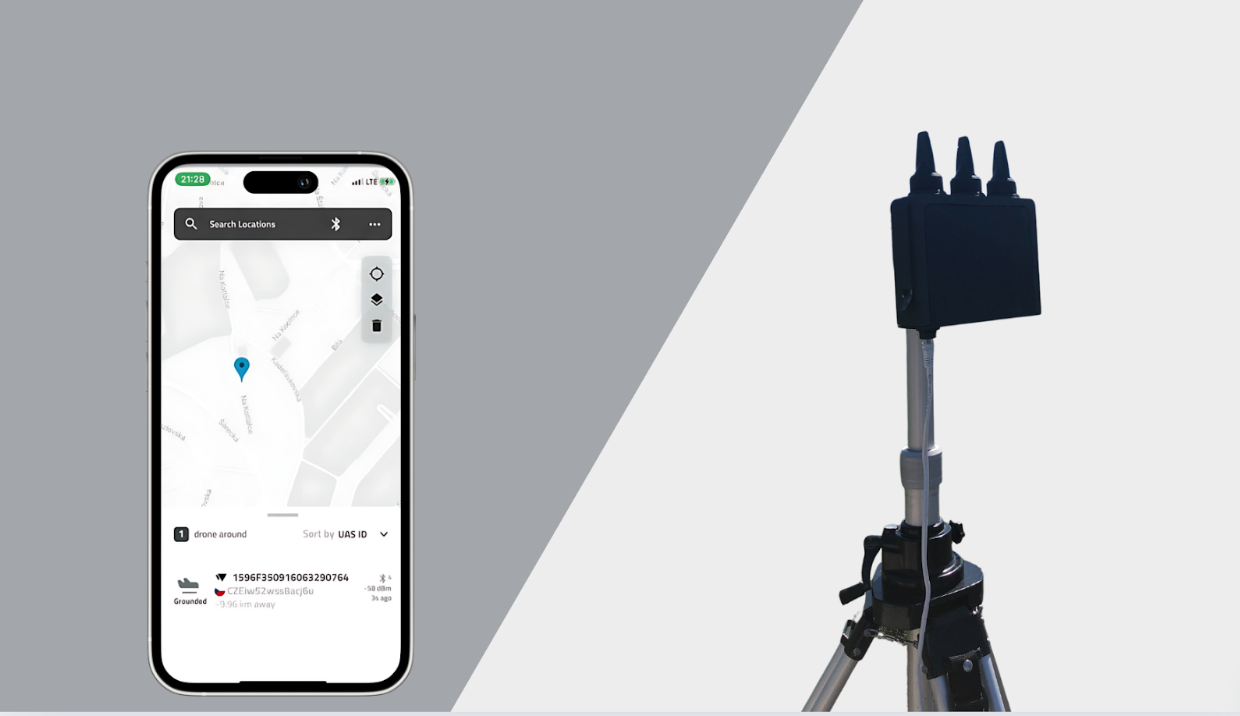

A drone detection system like AeroDefense's AirWarden™ can easily receive these RID broadcasts and verify that drones in the area are actively transmitting valid information. A system that can verify the RID will be a must for helping security teams distinguish between nefarious and hobbyist drone pilots.

It’s important to point out that a system designed specifically to ingest these RID, like an app for a cell phone or tablet, as described by the FAA can be easily defeated and is more of a convenience factor than an actual security measure. The RID system will have the same limitations as any drone detection system that is illegally decoding and demodulating signals transmitted by the drones or controllers.

Some of the limitations include the fact that the operator can modify these broadcasts to transmit the incorrect GPS coordinates of the device. If the drone doesn't have a GPS or doesn't have a stable GPS connection, the drone may not know where it is and therefore cannot broadcast its location. Someone can easily spoof an RID broadcast confusing the detection app or causing it to think the drone is in a completely different location or that there is a swarm of drones when there aren't any at all.

AirWarden has the ability to independently verify and track drone and pilot locations without reading signal content, such as GPS, which allows the system to be resilient to RID spoof attacks.

Conclusion

Current laws which have been in effect for five years require all drones over about half a pound to be registered with the FAA. The process only takes about five minutes and five dollars to complete. The question is how many people comply with these regulations and how many are blissfully unaware of the requirement altogether?

RID will be no exception. All drones that require registration will need RID transmitters. New drones will ship with this capability while existing and home-made ones likely will not meet the standard. The onus and burden are entirely on the owners of existing and home-made drones to seek out, purchase, install, and activate hardware that enables RID transmissions.

The addition of another transmitter will increase power consumption and therefore reduce battery life and flight time. Most familiar with drones know that one of the most important factors in a drone’s performance is the flight duration, so some pilots may be willing to take the risk of RID non-compliance.

For all the reasons previously mentioned, RID should not deter your organization from seeking information about drone detection systems if you experience drone threats.

Hobbyist drone pilots can be uninformed or slow to adhere to FAA laws, and nefarious ones will do just about anything to get around the law.

Furthermore, we are still a ways out from full implementation, and drone operators have even longer than manufacturers to comply with the regulation – 30 months from the effective date.